48,000-Year-Old Neanderthal Baby Teeth Reveal Weaning Patterns Similar to Modern Humans

A big landmark in human evolution is the moment a baby weans from milk to eating solid foods, and now a recent study shows that ancient Neanderthal babies might have taken a similar path.

The discovery gives groundbreaking insights into how these ancient humans lived, based on chemical analysis of Neanderthal baby teeth. And historically holding theories on how the species died out might even turn around, too.

The lives of young Neanderthals are still poorly understood by anthropologists, partly because the fossil record for these young hominids is so sparse. As a result, researchers have often flip-flopped on what they think early life looked like for these babies, and what set Homo sapiens apart.

The report, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, explains how Neanderthals’ milk teeth were studied by researchers. By comparing their results to humans who lived during the same period, the researchers have uncovered some striking similarities between our species.

Baby teeth are by their very nature temporary, but they’re actually an incredibly important indicator of an animal’s energy requirements, maternal lifestyle, and overall species longevity — ancient hominins included.

Alessia Nava is the co-first author of the paper and a post-doctoral anthropology researcher at the University of Kent. She explains that the similarities discovered between ancient humans and Neanderthals are not just an indicator of cultural practices, but evidence of similar physiological needs.

“In modern humans, in fact, the first introduction of solid food occurs at around 6 months of age when the child needs a more energetic food supply, and it is shared by very different cultures and societies,” Nava said in a statement. “[With our study], we know that also Neanderthals started to wean their children when modern humans do”.

Essentially, the results suggest that both our species weaned their babies and introduced foods at about the same time in their development.

DENTAL DISCOVERIES

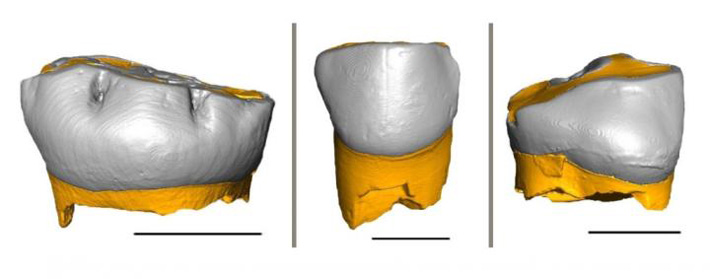

The researchers looked at three ancient Neanderthal milk teeth, found in a region of Italy. The teeth belonged to Neanderthal infants living between 45,000 and 70,000 years ago. They also analyzed the baby teeth of a single human child, who lived during the Upper Paleolithic era, which began about 40,000 years ago.

To read the histories hidden in these baby teeth, the scientists studied the tissues making up each tooth and performed chemical analysis. This allowed them to read the tree ring-like growth record left behind in the enamel of these teeth. This biological record also captures the moment the infant switches to eating solid food.

The researchers found that both the Neanderthal babies and the Upper Paleolithic human babies transitioned to eating solid foods at around the same age — between their fifth and sixth months of life.

ANCIENT FAMILY LIFE

The discovery tells researchers a lot more than just the feeding habits of these ancient babies, the study’s lead author and professor of physical anthropology at the University of Bologna, Stefano Benazzi, said in a statement.

These teeth hold important clues to the physiology and maternal experience of Neanderthals, too.

“This work’s results imply similar energy demands during early infancy and a close pace of growth between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals,” Benazzi said. “Taken together, these factors possibly suggest that Neanderthal newborns were of similar weight to modern human neonates, pointing to a likely similar gestational history and early-life ontogeny, and potentially shorter inter-birth interval”.

The researchers also gleaned more information about the Neanderthal family’s lifestyle — including that Neanderthal mothers may have tended to stay at home with their infants.

The findings also tell us more about how our ancient relatives died. This study overturns the consensus that weaning age — and its relationship with maternal fertility — somehow contributed to the Neanderthals’ eventual demise as a species. The idea here was that because Neanderthals weaned their children on a different timeline to humans, that could have affected their fertility rate.

But because Neanderthal babies appear to have similar energy requirements and weaning habits to ancient as well as modern humans, other factors — shorter overall lifespans, juvenile mortality, and cultural behaviour — may have been more likely culprits in precipitating Neanderthals’ extinction.

More research will be needed before we can truly piece together the complex history of these ancient hominins’ time on Earth. But the study adds to the mounting evidence that we are not so special a species as we like to think.