518 Million-Year-Old-Rocks Suggest Animal And Human Life May Have First Emerged In China

A new study based on an analysis of 518 million-year-old rocks that contain the oldest collection of fossils that researchers have on record. The researchers believe that Chengjian, a city in the mountainous Yunnan Province of China, is the origin of many of today’s species, including humans. This site is where complex organisms first developed, an event known as the ‘Cambrian Explosion’, a major time period in the history of the Earth.

The ancestors of many animal species alive today may have lived in a delta in what is now China, new research suggests.

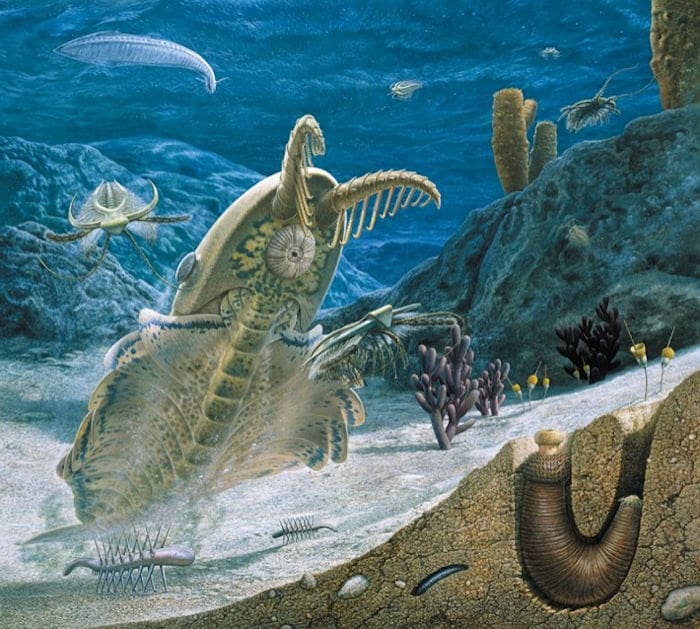

The Cambrian Explosion, more than 500 million years ago, saw the rapid spread of bilaterian species—symmetrical along a central line, like most of today’s animals (including humans).

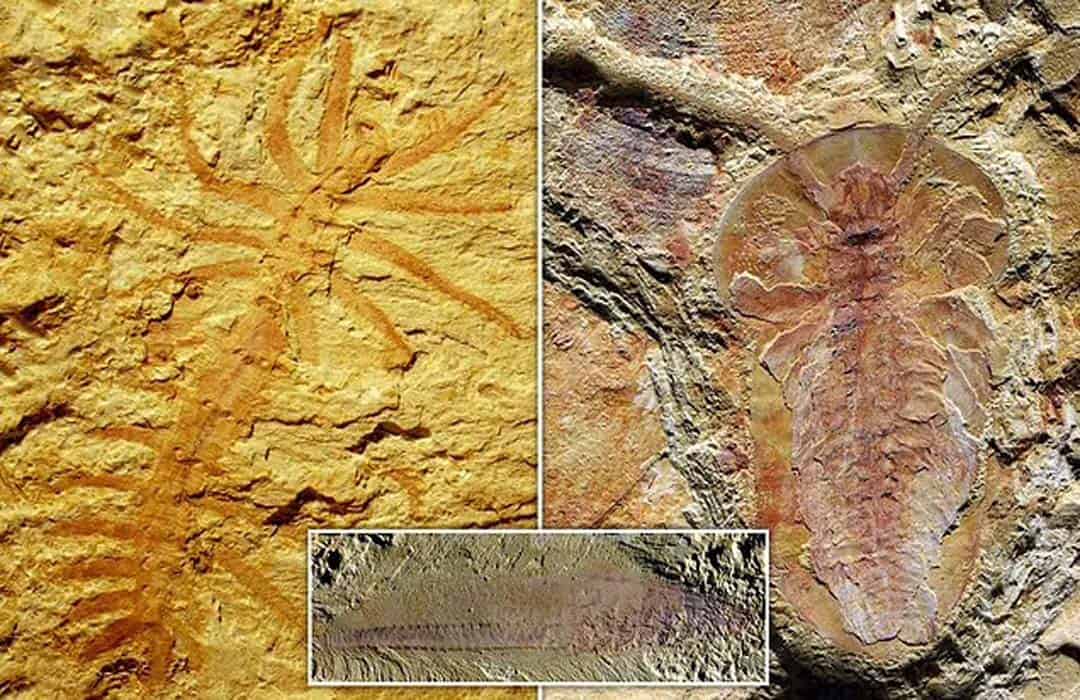

The 518-million-year-old Chengjiang Biota—in Yunnan, southwest China—is one of the oldest groups of animal fossils currently known to science and a key record of the Cambrian Explosion.

Fossils of more than 250 species have been found there, including various worms, arthropods (ancestors of living shrimps, insects, spiders, scorpions), and even the earliest vertebrates (ancestors of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals).

The new study finds for the first time that this environment was a shallow-marine, nutrient-rich delta affected by storm floods. The area is now on land in the mountainous Yunnan Province, but the team studied rock core samples that show evidence of marine currents in the past environment.

“The Cambrian Explosion is now universally accepted as a genuine rapid evolutionary event, but the causal factors for this event have been long debated, with hypotheses on environmental, genetic, or ecological triggers,” said senior author Dr. Xiaoya Ma, a palaeobiologist at the University of Exeter and Yunnan University.

“The discovery of a deltaic environment shed new light on understanding the possible causal factors for the flourishing of these Cambrian bilaterian animal-dominated marine communities and their exceptional soft-tissue preservation.

“The unstable environmental stressors might also contribute to the adaptive radiation of these early animals.”

Co-lead author Farid Saleh, a sedimentologist and taphonomic at Yunnan University, said: “We can see from the association of numerous sedimentary flows that the environment hosting the Chengjiang Biota was complex and certainly shallower than what has been previously suggested in the literature for similar animal communities.”

Changshi Qi, the other co-lead author, and a geochemist at Yunnan University added: “Our research shows that the Chengjiang Biota mainly lived in a well-oxygenated shallow-water deltaic environment.

“Storm floods transported these organisms down to the adjacent deep oxygen-deficient settings, leading to the exceptional preservation we see today.”

Co-author Luis Buatois, a palaeontologist and sedimentologist at the University of Saskatchewan, said: “The Chengjiang Biota, as is the case of similar faunas described elsewhere, is preserved in fine-grained deposits.

“Our understanding of how these muddy sediments were deposited has changed dramatically during the last 15 years.

“Application of this recently acquired knowledge to the study of fossiliferous deposits of exceptional preservation will change dramatically our understanding of how and where these sediments accumulated.”

The results of this study are important because they show that most early animals tolerated stressful conditions, such as salinity (salt) fluctuations, and high amounts of sediment deposition. This contrasts with earlier research suggesting that similar animals colonized deeper-water, more stable marine environments.

“It is hard to believe that these animals were able to cope with such a stressful environmental setting,” said M. Gabriela Mángano, a palaeontologist at the University of Saskatchewan, who has studied other well-known sites of exceptional preservation in Canada, Morocco, and Greenland.

Maximiliano Paz, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Saskatchewan who specializes in fine-grained systems, added: “Access to sediment cores allowed us to see details in the rock which are commonly difficult to appreciate in the weathered outcrops of the Chengjiang area.”

This work is an international collaboration between Yunnan University, the University of Exeter, the University of Saskatchewan, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of Lausanne, and the University of Leicester.

The research was funded by the Chinese Postdoctoral Science Foundation, the Natural Science Foundation of China, the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the George J. McLeod Enhancement Chair in Geology.