Archaeology breakthrough as ‘flabbergasted’ researchers make Cerne Abbas Giant Origin find

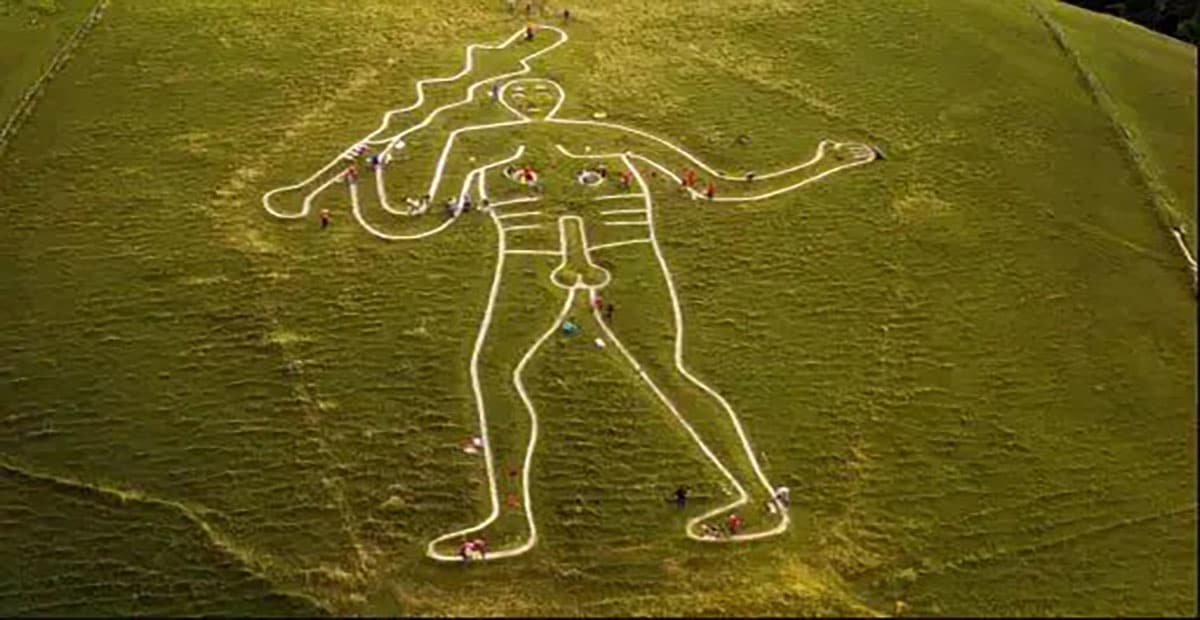

The Cerne Abbas Giant is a 180-foot-tall figure of a naked man wielding a large club, carved with chalk into a hilltop in Dorset, England. The figure’s generously sized erect phallus has earned it the nickname “Rude Man” and no doubt contributes to its popularity as a tourist attraction. Archaeologists have long speculated about exactly when, and why, the geoglyph was first created. Now, thanks to a new analysis of sediment samples, researchers have narrowed down the likely date for the Rude Man’s creation to the late Saxon period—a surprising result, since no other similar chalk figures in the region are known to date from that time period.

“This is not what was expected,” said geoarchaeologist Mike Allen, who has been working with the National Trust on the ongoing project to learn more about the Cerne Abbas Giant. “Many archaeologists and historians thought he was prehistoric or post-medieval, but not medieval. Everyone was wrong, and that makes these results even more exciting.” National Trust senior archaeologist Martin Papworth told the Guardian he was “flabbergasted” by the results, saying, “I was expecting the 17th century.”

In the 1990s, archaeologists relied on soil samples to date another well-known geoglyph—the 360-foot-long Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire—to between 1380 and 550 BCE. And the Long Man of Wilmington in East Sussex dates back to the 16th century. “Archaeologists have wanted to pigeonhole chalk hill figures into the same period,” said Allen. “But carving these figures was not a particular phase—they’re all individual figures, with local significance, each telling us something about that place and time.”

The Cerne Abbas Giant was formed by cutting trenches two feet deep into the steep hillside and then filling them with crushed chalk. Some scholars believed the giant might date back to the Iron Age as a fertility symbol. Local folklore holds that copulating on the giant’s crotch will help a couple conceive a child, and there is an Iron Age earthwork known as the Trendle at the top of the hill in which the giant has been carved. However, there is no mention of the figure in a 1540s survey of the Abbey lands, nor in a 1617 survey conducted by the English cartographer John Norden.

The earliest known written reference to the Cerne Giant appears in a 1694 warden’s account from St. Mary’s Church in Cerne Abbas, recording the cost of three shillings to repair “ye Giant.” There are also references to the figure in a 1734 letter by the then-Bishop of Bristol and a 1738 letter by antiquarian Francis Wise. The first survey to mention the giant was published in 1763 and included measurements and a drawing. After that, mention of the giant becomes far more common in the historical record.

Cerne Abbey was founded in 987 CE, and given the evidence for a medieval origin date, it’s possible that the giant was created to help convert local inhabitants from worshiping the early Anglo-Saxon god Heil (or Helith). However, Papworth is skeptical of this theory. “Why would a rich and famous abbey—just a few yards away—commission, or sanction, a naked man carved in chalk on a hillside?” he said.

Others have suggested the giant is a depiction of Hercules, citing evidence that the figure may have once worn a cloak, in keeping with the traditional depiction of the demigod. Or perhaps it was created in the 17th century as a parody of Oliver Cromwell, who was sometimes mocked as “England’s Hercules” by contemporaries.

Last year, the National Trust announced that soil samples taken from the figure included species of microscopic snails introduced to the region during the medieval period, in keeping with the new findings. For this latest analysis, the team relied upon a technique known as Optically Stimulated Luminescence, which involved subjecting the samples to laser light. That light released trapped particles, and by measuring their concentrations, it was possible to calculate when individual grains in those samples were last exposed to sunlight. That in turn enabled researchers to infer a likely date of origin.