In an 8,000-year-old Burial Archaeological Site in Sweden, Human Skeletons Mounted on Stakes Were Discovered

Researchers in Sweden have uncovered proof of a behavior never seen before in ancient hunter-gatherers: the mounting of decapitated heads onto stakes.

The grim discovery challenges our understanding of European Mesolithic culture and the way these early humans handled their dead.

Displaying decapitated heads on wooden stakes is something you would possibly expect from the Middle Ages, however as a new paper published in the journal Antiquity shows, it’s a practice that goes back much further in time than we thought. And in reality, the invention is the first evidence of this behavior among Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, who aren’t better known for dramatic displays of this sort.

The researchers who found the skulls are at a loss to clarify why these ancient Europeans would have mounted them on posts, but the reason may not be as sinister as it appears.

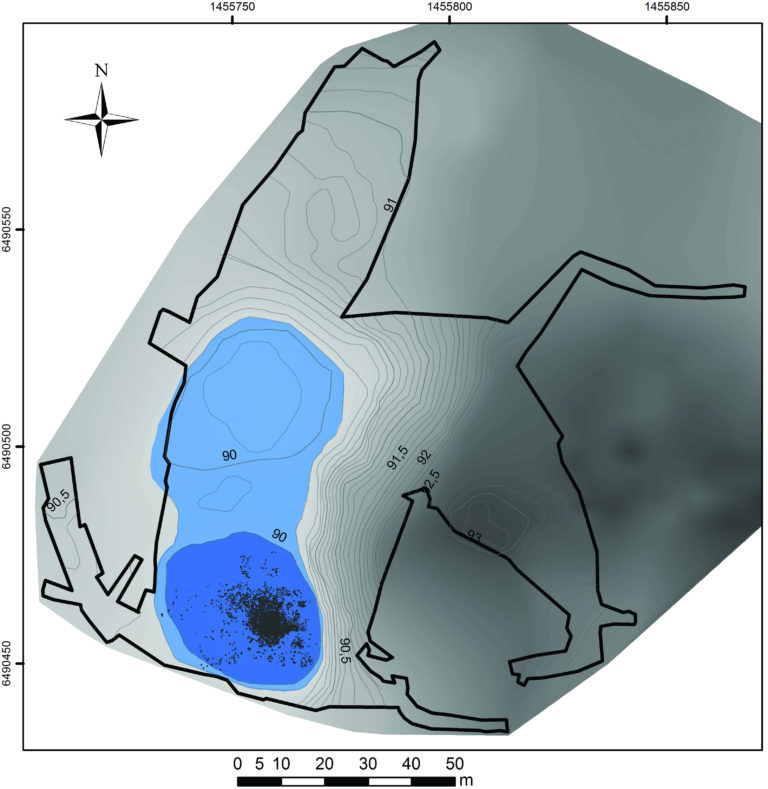

Researchers from Stockholm University and the Cultural Heritage Foundation found the skulls at the bottom of what was once a lake, at the Kanaljorden excavation site in Sweden near the Motala Ström river. The human remains, found at an 8,000-year-old graveyard, were uncovered back in 2011, and therefore the details of the scientific analysis were finally published today.

This Mesolithic site has been under investigation since 2009, with archaeologists pulling up butchered animal bones, tools fashioned from antlers, wooden stakes, and bits of human skulls. The ancient Scandinavians who used to live at the location survived by hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Due to the poor archaeological record, scientists understand very little about the sociocultural aspects of these people.

Swedish archaeologists found the remains of ten individuals—nine adults and one infant— deliberately placed atop a densely packed layer of large stones. one in all adult males was older, most likely in his fifties when he died. Two were young, somewhere between the ages of twenty to thirty-five.

Two were identified as female, and four as male. The nearly-complete skeleton of the infant suggests it was either stillborn or died shortly once birth.

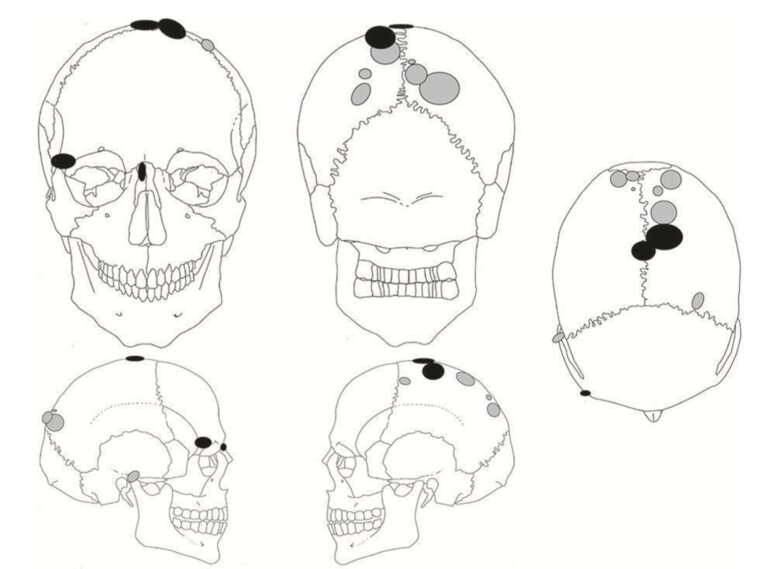

All of the adult skulls exhibited signs of blunt force trauma before death. The majority of those injuries were near the top of the head, above the so-called hat brim line. For a few reasons, the injuries varied according to sex; the two females had injuries at the back and right side of their heads, whereas the males displayed signs of a single traumatic event to the top of the head or face. a number of the skulls showed signs of prior injuries and subsequent healing.

None of the skulls were found with mandibles, which the researchers suspect had something to do with ancient burial practices. They don’t understand what weapon or weapons were used to inflict this damage, and the wounds couldn’t be tied to cause death—but the injuries weren’t subtle.

“Though the lesions were not fatal, they must have affected the people—induced pain, bleeding, and a risk of secondary infections,” study author and Stockholm University archeologist Anna Kjellström told me.

“Furthermore, even less severe head trauma could cause loss of consciousness, internal bleeding, or maybe permanent mental impairment.”

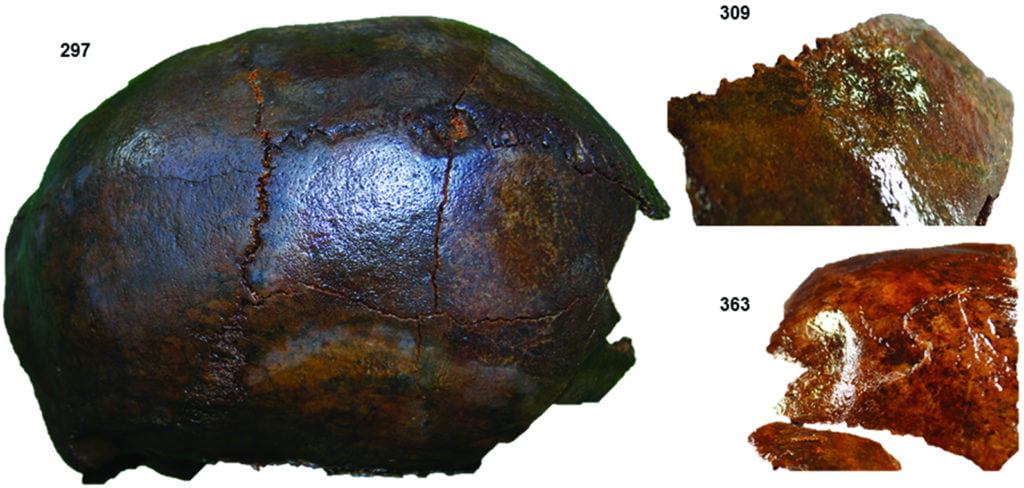

To the surprise of the researchers, 3 of the male skulls exhibited signs of sharp force trauma after death. Incredibly—and after 8,000 years—the well-preserved remains of wooden stakes were found dislodged within two of the skulls, suggesting they’d been mounted prior to being deposited in the lake.

In one case, the wooden spike was still sticking out of the bone. The stakes were inserted through the large oval opening at the lowest of the skull (foramen magnum) reaching through the top of the skull.

In all, the researchers managed to uncover four hundred intact and fragmentary bits of wooden stakes at the site, a number of which may have been used to mount objects that have since fallen off. Other stakes could are used for construction purposes, such as partitions or fences.

So what can account for all of this? To summarize the researchers’ conclusions:

To be fair, the researchers did posit some explanations, however, they weren’t willing to commit to a particular interpretation. The sample size is way too little, and since this is literally the first case of its kind among Mesolithic humans, the scientists had nothing to compare it to.

The blunt force trauma injuries say the researchers, could have happened by accident (very unlikely given the specificity and recurrence of the injuries), social violence, forced abduction, spousal abuse, warfare, or socially sanctioned non-lethal violence. as a result of these injuries were differentiated by sex, the victims could a part of a stigmatized group.

One possibility is gender-related violence—a society wherever men and women were treated or behaved differently from each other. Or these people were slaves—a highly unlikely scenario, say the researchers, as that’s unheard of among hunter-gatherers who lacked the resources (and possibly motivations) to maintain a slave category. More realistically, the injuries were inflicted during raiding and warfare. As the authors write:

“The gender-related trauma pattern… is reminiscent of patterns determined among North American prehistoric hunter-gatherers, which have been interpreted as a result of different roles and behavior in combat. This could be associated with how people of different gender and age may play different roles in a combat situation.“

Finally, the blunt force trauma injuries could have been inflicted for cultural reasons, as hard as that’s to believe.

“We have not found any clear indications that recommend that these individuals had another affinity or social status than people buried close to this site,” Kjellström told me.

“We wish to point out that the injuries may not necessarily have occurred under hostile actions. as an example, there are anthropological descriptions wherever lesions on participants occur from ritual ceremonies. This complicates the interpretation of who these people were.”

As for the handling of the bodies after death and therefore the mounting of heads on wooden stakes, that’s definitely weird. Mesolithic hunter-gatherers are not known to remove body elements like this; their grave sites show respect for bodily integrity after death. That said, groups that appeared much later in history did behead their enemies, generally using the skulls of the vanquished as a trophy or warning.

Historical examples include European colonists mounting the skulls of dead indigenous peoples, or indigenous peoples using skulls in both burial rituals and as trophy displays. It’s not clear what the context was during this case. All we know is that, for whatever reason, these heads were mounted on the stakes, left there for a relatively short amount of time, and then deliberately laid to rest in the shallow lakebed on the rocks.

“The fact that 2 crania were mounted suggests that they have been on display, in the lake or elsewhere,” said Kjellström. In general, skulls without jaws were chosen for the display. “Since we did not find any sharp trauma showing active making an attempt to separate the lower jaw from the skulls, this indicates that the people much likely were buried in another place before the depositions… One interpretation could be that this is an alternative funeral act.”

We won’t understand more until additional research is done, and until more bones and artifacts are uncovered. However, one thing’s for sure—we’ll never look at hunter-gatherers the same way again.