1,000-Years-Ago Ancient Canoe Burial Unveils Patagonia’s Pre-Hispanic Funeral Rituals

Up to 1,000 years ago, mourners buried a young woman in a ceremonial canoe to represent her final journey into the land of the dead in what is now Patagonia, a new study finds.

The discovery reaffirms ethnographic and historical accounts that canoe burials were practiced throughout pre-Hispanic South America and refutes the idea that they may have been used only after the Spanish colonization, according to the authors of the study.

“We hope this investigation and its results will resolve this controversy,” said archaeologist Alberto Pérez, an associate professor of anthropology at the Temuco Catholic University in Chile and the lead author of the study, published Wednesday (Aug. 24) in the journal PLOS One.

Canoe burials are well attested and are still practiced in some areas of South America, Pérez told Live Science. But because wood rots rapidly, the new finding is the first known evidence of the practice from the pre-Hispanic period. “The previous evidence was important and was based on ethnographic data, but the evidence was indirect,” he said.

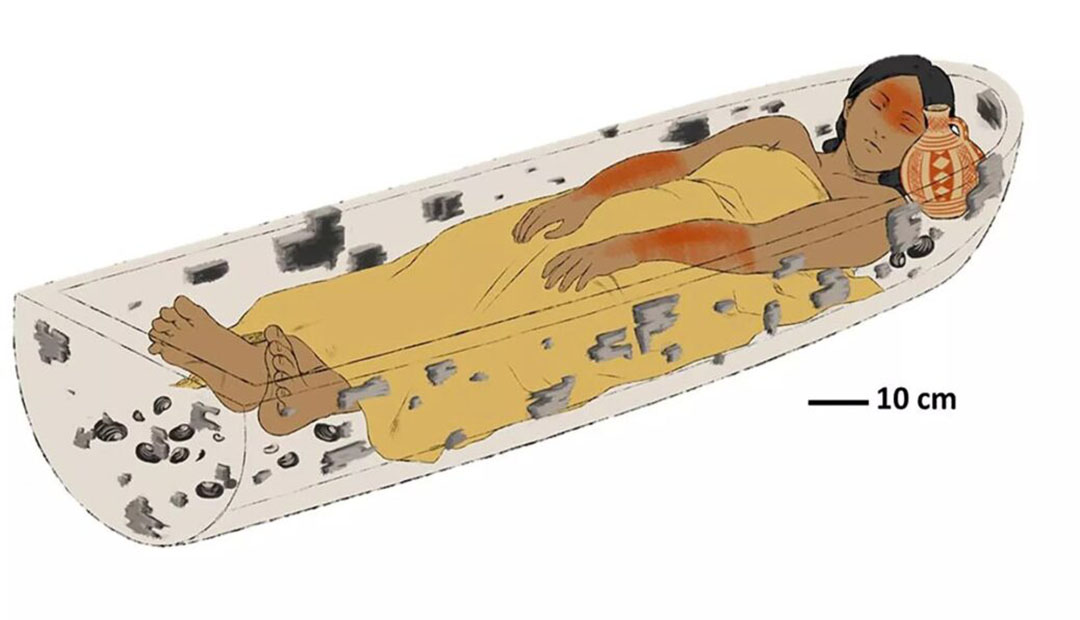

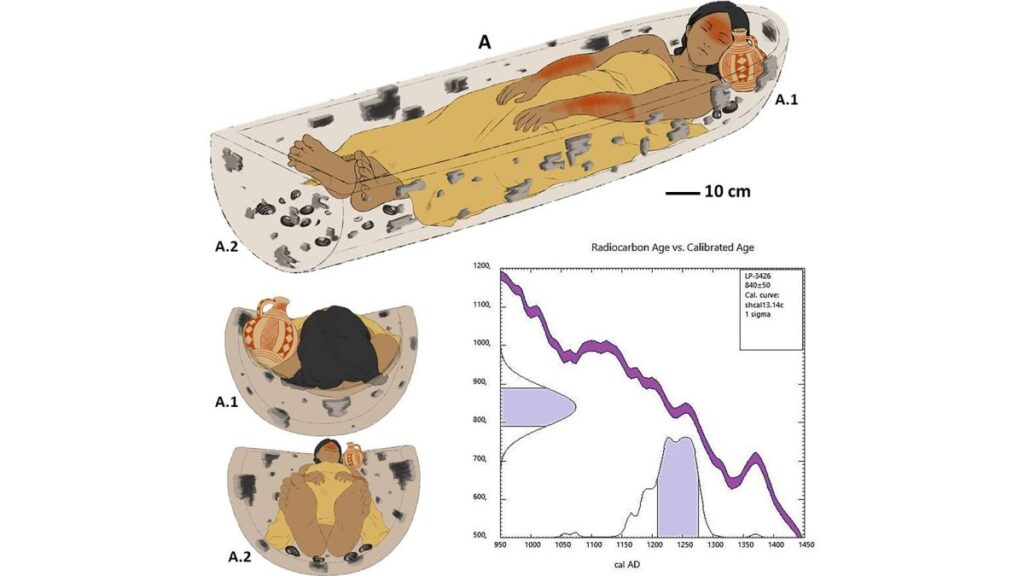

The burial described in the study, at the Newen Antug archaeological site near Lake Lacár in western Argentina, indicates that mourners buried the woman on her back in a wooden structure crafted from a single tree trunk that had been hollowed out by the fire.

The same burning technique has been used for thousands of years to make “dugout” canoes known as “wampos” in the local Mapuche culture, and evidence suggests that Indigenous people prepared the women remains so that she could embark on a final canoe journey across mystical waters to her final abode in the “destination of souls,” Pérez said.

Pre-Hispanic burial

The woman’s grave is the earliest of three known pre-Hispanic burials at the Newen Antug site, which archaeologists excavated between 2012 and 2015 before a well was built at the location, which is on private land. The location is at the northern extreme of the region known as Patagonia, which consists of the temperate steppes, alpine regions, coasts and deserts of the southern part of South America.

Radiocarbon dating indicates the woman was buried more than 850 years ago and possibly up to 1,000 years ago, while her sex and age at death — between 17 and 25 years old — were estimated from her pelvic bones and the wear on her teeth, according to the study. (Evidence suggests the Mapuche have lived in the region since at least 600 B.C.)

A pottery jug decorated with white glaze and red geometric patterns, placed in the grave by her head, suggests a connection with the “red on white bichrome” tradition of pre-Hispanic ceramics on both sides of the Andes mountains, the researchers found. This is the earliest known example of this type of pottery being used as a grave gift, according to the study.

Given its age and the humid climate, the burial canoe has rotted away, and only fragments of wood remain. But tests suggest that the fragments came from the same tree — a Chilean cedar (Austrocedrus chilensis) — and that it had been hollowed out with fire.

Shells found in the grave show that her body was placed directly on a bed of Diplodon chilensis, a type of freshwater clam that was likely brought from the shores of Lake Lacár more than 1,000 feet (300 meters) away, the researchers wrote.

In addition, the position of the body — with the arms gathered above the torso, and the head and feet raised — indicates that the woman was buried inside a concave structure with thicker walls at the ends, which correspond to the bow and stern of a canoe, Pérez said.

Taken together, these aspects suggest the woman was interred in a traditional canoe burial representing the Mapuche belief that a soul must make a final boat journey before it arrives in the land of the dead. “The material evidence all goes in the same direction, and there is a whole battery of ethnographic and historical information that accounts for it,” Pérez told Live Science in an email.

Destination of souls

According to Mapuche belief, the destination of the dead’s souls was “Nomelafken” — a word in the Mapuche language that translates to the “other side of the sea” — and the newly dead would make a metaphorical boat journey for up to four years before they arrived at a mythical island called Külchemapu or Külchemaiwe, Pérez and his colleagues wrote in the study.

A historical report from the 1840s by the Chilean politician Salvador Sanfuentes remarked that local people “site the graves of their dead on the bank of a stream to allow the current to carry the soul to the land of souls” and that ceremonial canoes were buried as coffins to carry the dead on this journey, the researchers wrote.

The metaphor of the recently deceased making such a canoe journey to a final destination seems to have been prevalent throughout South America in pre-Hispanic times, and possibly for thousands of years, Pérez noted.

“We infer that this was a widespread practice on the continent, although it is little known to archaeology due to conservation problems,” such as the degradation of wood in humid climates, he said. “The antiquity of these practices is uncertain, but we know such navigation technologies were used there more than 3,500 years ago, so we can estimate that date as a potential time limit.”

The new study has great scientific importance for archaeological and anthropological research in the Patagonia region, said Nicolás Lira, an assistant professor of archaeology, ethnography and prehistory at the University of Chile who wasn’t involved in the research.

“The findings … are of exceptional preservation for the humid environment of the region, where rivers and lakes shape the landscape in an interconnected [river] system that facilitated and encouraged navigation,” Lira told Live Science in an email.

Juan Skewes, an anthropologist at Alberto Hurtado University in Chile who wasn’t involved in the study, said the Newen Antug burial was “strong evidence” of a shared cultural tradition between the east and west “slopes” of the Andes.

Meanwhile, historical and ethnographic records suggest such canoe burials represented a symbolic relationship between the Mapuche people and bodies of water, but that relationship wasn’t their only consideration, Skewes said. For example, “trees are part of almost every aspect of the Mapuche’s daily life, Skewes said. “Aside from having associations with mortuary practices, they are linked to childbirth and to the memories of the dead.” That might mean that the construction of a burial wampo from a single tree could have had extra meaning, in addition to the canoe’s symbolic function during the final voyage of the dead, he said.