Ancient Shells: The Evolution of Personal Identity Over 100,000 Years Ago

Scientists have found evidence suggesting the ancient use of ochre in Africa and Europe indicates that body painting, clothing decoration, and tattooing may date back to more than 300,00 years ago, or perhaps even 500,000 years ago. But when did our ancestors start showing signs of the early creation of personal identity?

According to scientists, early ancestors collected eye-catching shells that radically changed the way we looked at ourselves and others. A new study confirms previous scant evidence and supports a multistep evolutionary scenario for the culturalization of the human body.

The study, which was conducted by Francesco d’Errico, Karen Loise van Niekerk, Lila Geis and Christopher Stuart Henshilwood, from Bergen University in Norway and the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Johannesburg, South Africa, is published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Its significant findings provide vital information about how and when we may have started developing modern human identities.

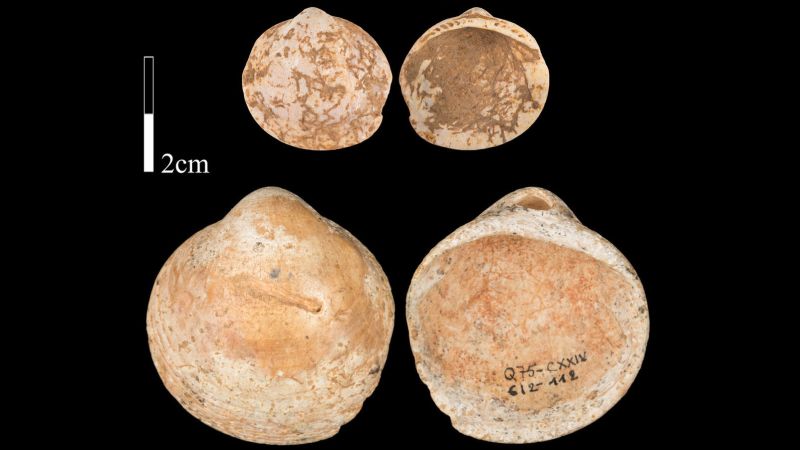

“The discovery of eye-catching unmodified shells with natural holes from 100,000 to 73,000 years ago confirms previous scant evidence that marine shells were collected, taken to the site and, in some cases, perhaps worn as personal ornaments.

This was before a stage in which shells belonging to selected species were systematically, and intentionally perforated with suitable techniques to create composite beadworks,” says van Niekerk.

The shells were all found in the Blombos Cave, on the southern Cape of South Africa’s coastline. Similar shells have been found in North Africa, other sites in South Africa and the Mediterranean Levant, which means that the argument is supported by evidence from other sites, not just Blombos Cave.

Confirms scant evidence of early beadwork

In other words, the unperforated and naturally perforated shells provide evidence that marine shells were collected and possibly used as personal ornaments before the development of more advanced techniques to modify the shells for use in beadworks around 70,000 years ago.

Van Niekerk says that they know for sure that these shells are not the remains of edible shellfish species that could have been collected and brought to the site for food.

“We know this because they were already dead when collected, which we can see from the condition of most of the shells, as they are waterworn or have growths inside them, or have holes made by a natural predator or from abrasion from wave action.”

The researchers measured the size of the shells and the holes made in them, as well as the wear on the edges of the holes that developed while the shells were worn on strings by humans. They also looked at where the shells came from in the site to see whether they could be included in different groups of beads found close together that could have belonged to single items of beadwork. These techniques provide insights into the potential use of these shells for symbolic purposes.

Early signs of possible creation of identity

Van Niekerk says that they identified 18 new marine snail shells from 100,000 to 70,000 years ago, that could have been used for symbolic purposes, and proposed a multistep progression for the culturalization of the human body with roots in the deep past.