Archaeologist Discovered Viking Ship Found Under the Ground in Norway

Archaeologists in Norway using ground-penetrating radar have detected one of the largest Viking ship graves ever found. Archaeologists have found the outlines of a Viking ship buried not far from the Norwegian capital of Oslo.

The 65-foot-long ship was covered over more than 1,000 years ago to serve as the final resting place of a prominent Viking king or queen. That makes it one of the largest Viking ship graves ever discovered.

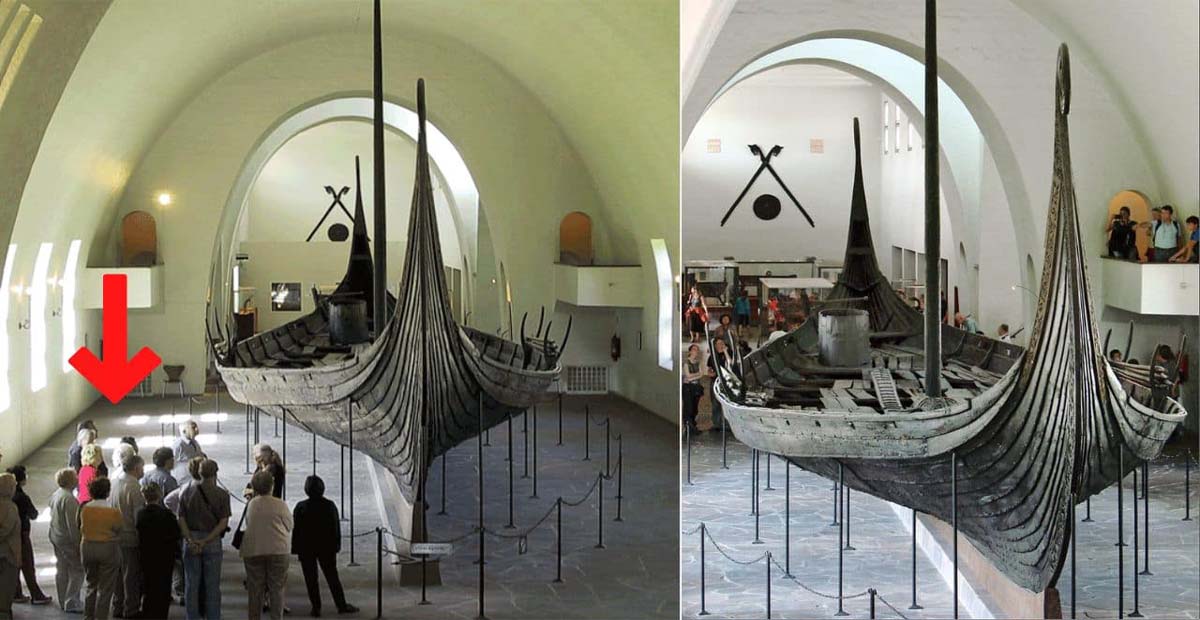

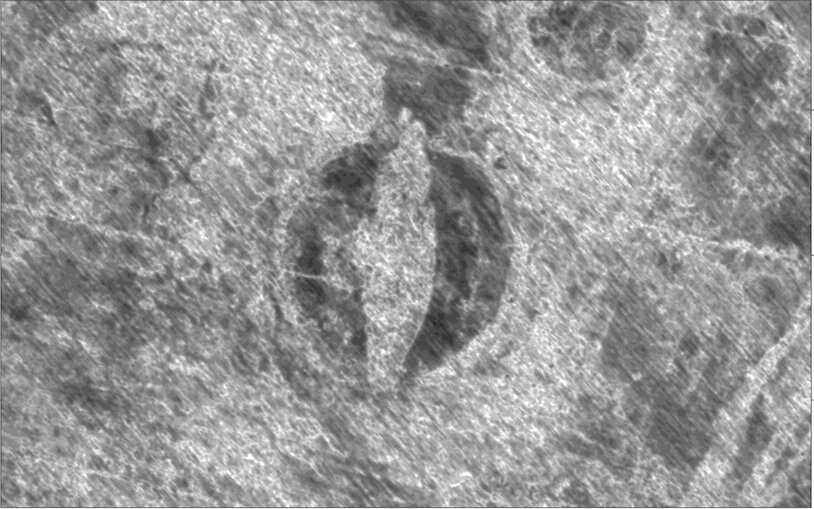

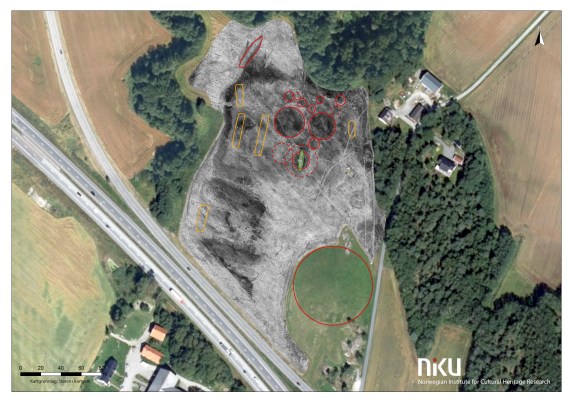

An image generated by ground-penetrating radar reveals the outlines of a Viking ship within a burial mound. Experts say intact Viking ship graves of this size are vanishingly uncommon. “I think we could talk about a hundred-year find,” says archaeologist Jan Bill, curator of Viking ships at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. “It’s quite spectacular from an archaeology perspective.”

The site where the ship grave was discovered is well-known. A burial mound 30 feet tall looms over the site, serving as a local landmark visible from the expressway just north of the Swedish border.

But archaeologists thought any archaeological remains in the nearby fields must have been destroyed by farmers’ plows in the late nineteenth century.

Then, this spring, officials from the surrounding county of Ostfold asked experts from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Research to survey the fields using a large ground-penetrating radar array.

They were able to scan the soil underneath almost 10 acres of farmland around the mound. Underneath, they found proof of 10 large graves and traces of a ship’s hull, hidden just 20 inches beneath the surface.

Knut Paasche, head of the archaeology department at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Research and executive of the recent work at the site, estimates the ship was at least 65 feet long.

It appears to be well preserved, with clear outlines of the keel and the first few strakes, or lines of planking, visible in the radar scans. The ship would have been dragged onshore from the nearby Oslo fjord. At some point during the Viking Age, it was the final resting place of someone powerful.

“Ships like this functioned as a coffin,” says Paasche. “There was one king or queen or local chieftain on board.”

Whoever was buried in the ship was not alone. There are traces of at least 8 other burial mounds in the field, some almost 90 feet across. Three large longhouses—one 150 feet long—are also visible underneath the site’s soil, together with a half dozen smaller structures.

Archaeologists hope future unearthings will help date the mounds and the longhouses, which may have been built at different times. “We can not be sure the houses have the same age as the ship,” Paasche says.

Paasche plans to return to the site next spring to lead more sophisticated scans, including surveying the site with a magnetometer and perhaps digging test trenches to see what condition the ship’s remains are in.

If there is wood from the ship’s hull preserved beneath the ground, it could be used to date the find more decisively.

The chances of finding a king’s fortune are slim. Because they were so prominent in the landscape, many Viking Age burials were robbed centuries ago, long before they were leveled by Nineteenth-century farmers.

But “it would be very exciting to see if the burial is still intact,” says Bill. “If it is, it could be holding some very interesting finds.”