California Gold Mine Reveals 40 Million-Year-Old Tools Were Found

At Table Mountain and other locations in the gold mining region around the middle of the nineteenth century, miners discovered hundreds of stone artifacts and human bones buried deep inside their tunnels. Experts claim that these bones and artifacts were found embedded in layers from the Eocene epoch (38-55 million years).

The Auriferous Gravels of the Sierra Nevada of California, written by Dr. J. D. Whitney, the leading government geologist in California, was published in 1880 by Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Comparative Zoology.

However, because the information went against accepted Darwinist theories on human origins, it was excluded from scholarly discussions. In 1849, gold was found in the gravels of old riverbeds on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, drawing large numbers of rowdy adventurers to settlements including Brandy City, Last Chance, Lost Camp, You Bet, and Poker Flat.

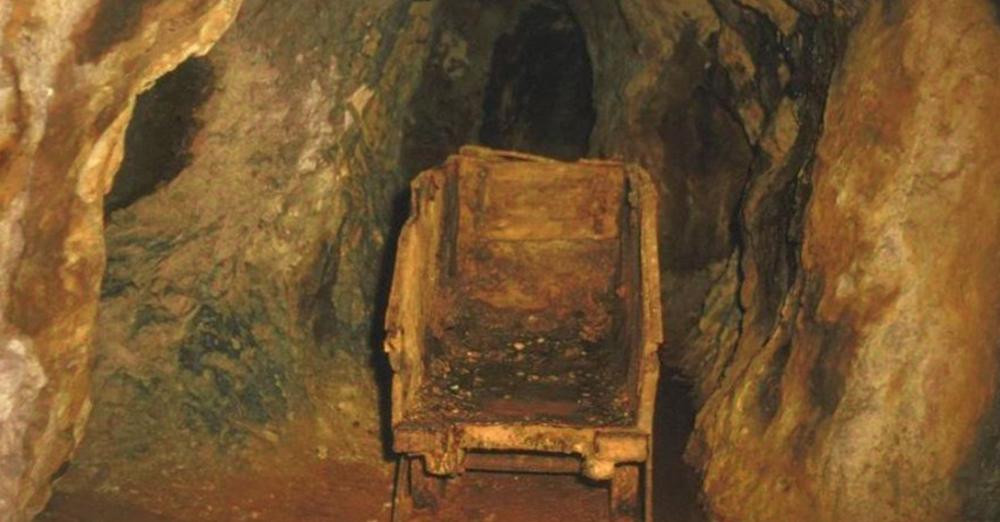

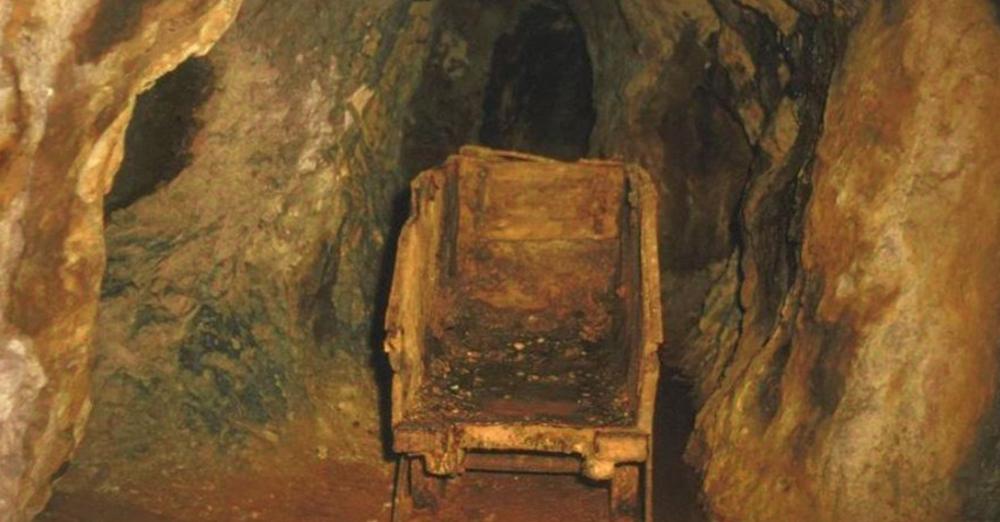

Initially, solitary miners searched for flakes and nuggets among the gravel that had made their way into the present-day streambeds. Auriferous (gold-bearing) gravels were quickly washed from hillsides by high-pressure water jets while other gold-mining businesses bored holes into mountainside deposits and followed the gravel deposits wherever they led.

The miners found hundreds of stone items as well as human fossils. The scientific community received the most crucial information from Dr. J. D. Whitney.

Artifacts from hydraulic mining and surface deposits were of questionable age, while deep mine shaft and tunnel artifacts could be more accurately dated. According to J. D. Whitney, the geological evidence revealed that the auriferous gravels were at least Pliocene in age.

However, according to modern geologists, some of the gravel layers are Eocene in origin. In Tuolumne County’s Table Mountain, several holes were dug, traveling through thick strata of latite, a basaltic volcanic substance, before arriving at the gravels containing gold.

In other instances, the tunnels stretched hundreds of feet horizontally beneath the latite top. The age of findings from the gravels directly above the bedrock might be between 33.2 and 55 million years old, and those from other gravels could be between 9 and 55 million years old.

According to William B. Holmes, a physical anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution, “If Professor Whitney had fully appreciated the story of human evolution as it is understood today, he would have hesitated to announce the conclusions formulated, notwithstanding the imposing array of testimony with which he was confronted.” Or, to put it another way, the theory had to be rejected if the evidence did not support it, which is exactly what happened.

The Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, still has some of the items Whitney mentioned on the exhibit. Darwinism and other isms affected how archaeological evidence was handled in Hueyatlaco, Mexico. Archaeologists working under the direction of Cynthia Irwin-Williams found stone tools there in the 1970s that were associated with bones from butchered animals.

A group of geologists, including Virginia Steen-McIntyre, dated the location. The age of the site was established using four different techniques: stratigraphic analysis, zircon fission track dating on volcanic layers above the artifact layers, tephra hydration dating of volcanic crystals found in volcanic layers above the artifact layers, and uranium-series dates on butchered animal bones.

The reason the archaeologists were hesitant to put an age on the site was because they thought that (1) no humans were around 250,000 years ago anyplace on the earth, and (2) no humans visited North America until at most 15,000 or 20,000 years ago.

At Table Mountain and other locations in the gold mining region around the middle of the nineteenth century, miners discovered hundreds of stone artifacts and human bones buried deep inside their tunnels.