Jaw-Dropping Discovery: 18th-Century Mummified Monks Revealed Suffering From Tuberculosis Infections

Scientists recently examined tissue samples from tuberculosis-infected bodies that were naturally mummified in a church crypt in Vac, Hungary.

Researchers found that tuberculosis that killed them in the 1700s derived from an ancestral strain of the bacteria dating from Roman times still circulating in Europe in the 18th century.

The bodies, excavated in 1994, were naturally mummified by extremely dry air and pine chips in coffins. The pine chips have natural anti-microbial agents and absorbed moisture.

The bodies had been buried in a church crypt between 1731 and 1838. They were Catholics, buried fully clothed, and many of them were rich, says an article in Phys.org. Their clothing too was preserved by the dry air.

Vac is just north of the Hungarian capital of Budapest. A construction worker in the Dominican church in Vac tapped on a wall and heard a hollow sound. He pulled out a brick and saw the caskets.

Experts found more than 200 bodies, 26 of which were tested because they had signs of tuberculosis infection. Eight of the bodies yielded tissue samples from which researchers were able to do genetic sequencing of the tuberculosis germs.

“What emerged is a tableau of a disease that fully lives up to its reputation in folklore,” wrote Phys.org. “TB was raging in 18th-century Europe, even before urbanization and crowded housing made it a killer on a much greater scale, the investigators found.”

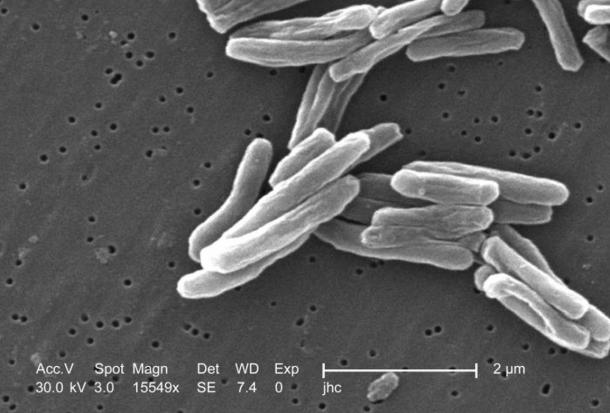

The German microbiologist Robert Koch was the first to describe Mycobacterium tuberculosis, in 1882. Koch said consumption, as people called it then, killed one in seven people. The disease is still a serious problem, but the World Health Organization reports deaths from it have been decreasing in recent decades.

In the church in Vac, the dead people’s names and how they died were recorded in documents. Phys.org said that makes the bodies a valuable resource for people who study diseases because the combination gives evidence about how TB and disease spread centuries ago.

“Microbiological analysis of samples from contemporary TB patients usually report a single strain of tuberculosis per patient,” Mark Pallen of the England’s University of Warwick medical school, told Phys.org. Pallen was the chief researcher in the new study. “By contrast, five of the eight bodies in our study yielded more than one type of tuberculosis—remarkably, from one individual, we obtained evidence of three distinct strains.”

All eight bodies were carriers of a particularly virulent strain of tuberculosis called Lineage 4. Still today this strain infects more than 1 million people in the Americas and Europe per year.

“(It) confirmed the genotypic continuity of an infection that has ravaged the heart of Europe since prehistoric times,” Pallen said.

Researchers built a family tree of the TB bug and ascertained its bacterial ancestor dating to the late Roman period. This dating seems to lend credence to recent estimates that tuberculosis emerged in humans about 6,000 years ago, Phys.org said. Previous research theorized tuberculosis emerged in humans tens of thousands of years ago.

The World Health Organization reports that about one-third of humans are infected with tuberculosis bacteria, but only a small percentage will become ill from it. In 2013, about 9 million people became sick with the disease worldwide. Approximately 95 percent of TB deaths are in middle- and low-income nations.

While the disease is a serious problem, the threat from it appears to be decreasing somewhat.

“The number of people falling ill with TB is declining and the TB death rate dropped 45 percent since 1990. For example, Brazil and China have shown a sustained decline in TB cases over the past 20 years. In this period China has had an 80% decline in deaths,” WHO reports.