Lost City of Alexander the Great Discovered in Iraq Using Old Spy Footage

The ‘lost city’ of Alexander the Great was a mystical place where people drank wine and naked philosophers exchanged wisdom, ancient accounts claim. Now, nearly 2,000 years after the great warrior’s death, archaeologists believe the city may have finally been discovered in Iraq.

Since looking at declassified American spy recordings from the sixties, analysts have first found the old remains in the Iraqi settlement known as Qalatga Darband. The images were made public in 1996 but, due to political instability, archaeologists were unable to explore the site properly for years.

Now archaeologists have discovered that there has been a city during the first and second centuries BC that had heavy Greek and Roman influences, with more modern drone footage and on-site work.

They believe Alexander the Great founded it in 331 BC and later settled in the city with 3,000 veterans of his campaigns. Undefeated in battle, Alexander had carved out a vast empire stretching from Macedonia, Greece in Europe, to Persia, Egypt and even parts of northern India by the time of his death aged 32.

Researchers believe Qalatga Darband – which roughly translates from Kurdish as ‘castle of the mountain pass’ – is on the route Alexander of Macedon took to attack Darius III of Persia in 331 BC. The city may have served as an important meeting point between East and West. It is 6 miles (10km) south-east of Rania in Sulaimaniya province in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Researchers at the British Museum first explored the site using spy footage of the area from the 1960s. An archaeological dig was not possible when Saddam Hussein controlled Iraq. But more recently improved security has allowed the British Museum to explore the site as a way of training Iraqis to rescue areas damaged by Islamic State. As well as on-site work, the Museum has also been able to capture drone footage of the area.

‘We got coverage of all the site using the drone in the spring — analysing crop marks hasn’t been done at all in Mesopotamian archaeology’, lead archaeologist John MacGinnis told The Times.

‘It’s early days, but we think it would have been a bustling city on a road from Iraq to Iran. ‘You can imagine people supplying wine to soldiers passing through’, he said.

‘Where there are walls underground the wheat and barley don’t grow so well, so there are colour differences in the crop growth’.

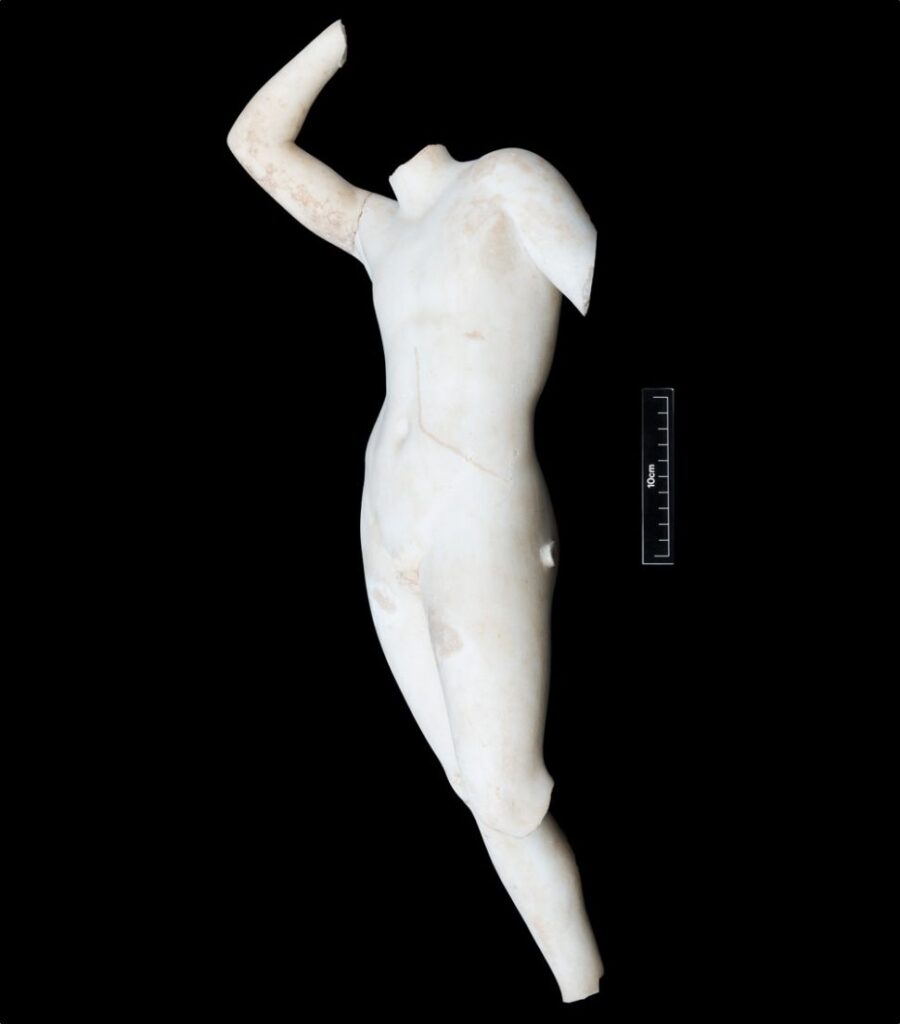

From the excavation work, they discovered an abundance of terracotta roof tiles and Greek and Roman statues, suggesting the city’s early residents were Alexander’s subjects.

Among the statues they found was a female figure believed to be Persephone, the Greek goddess of vegetation, and the other is believed to be Adonis, a symbol of fertility.

They also discovered a coin of Orodes II, who was king of the Parthian from 57 BC to 37 BC. On its western flank, the city was protected by a large fortification which ran from the river to the mountain.

It is situated on a large open site of around 60 hectares (148 acres) on a natural terrace. The 1960s Corona spy satellite footage showed a large square building, potentially believed to be a fort, according to a British Museum blog.

Farmers in the area had also found remains of big buildings and a large fortified wall. There were several limestone blocks, believed to be wine or oil presses. Meanwhile, excavation of a mound at the southern end of the site revealed a monument that could have been a temple for worship.

Fieldwork started in the autumn of 2016 and is expected to last until 2020. The project, which was part of the government-funded Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Programme, has been possible due to improved security in the country.

It is part of a £30 million ($40 million) government plan to help Iraq rebuild historical sites destroyed by Islamic State. This fund is designed to counter the destruction of heritage in cultural zones by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. The programme involves bringing groups of Iraqi archaeologists to London for eight weeks of training at the British Museum.

They are then sent to excavations in the field for six additional weeks where they learn how to do drone surveys and 3D scanning. The team now wants to find linguistic evidence to confirm their findings. Earlier this year archaeologists believe they found the last will of Alexander the Great – more than 2,000 years after his death.

A London-based expert David Grant claimed to have unearthed the Macedonian king’s dying wishes in an ancient text that has been ‘hiding in plain sight’ for centuries.

The long-dismissed last will divulged Alexander’s plans for the future of the Greek-Persian empire he ruled. It also reveals his burial wishes and discloses the beneficiaries of his vast fortune and power. Evidence for the lost will can be found in an ancient manuscript known as the ‘Alexander Romance’, a book of fables covering Alexander’s mythical exploits.

Likely compiled during the century after Alexander’s death, the fables contain invaluable historical fragments about Alexander’s campaigns in the Persian Empire.