Mystery Surrounds the Sudden Decline of Africa’s Ancient Baobab Trees

Africa’s iconic baobab trees are dying, and scientists don’t know why. In a study intended to examine why the trees are so long-living, researchers made the unexpected finding that many of the oldest and largest of the trees have died in the past decade or so.

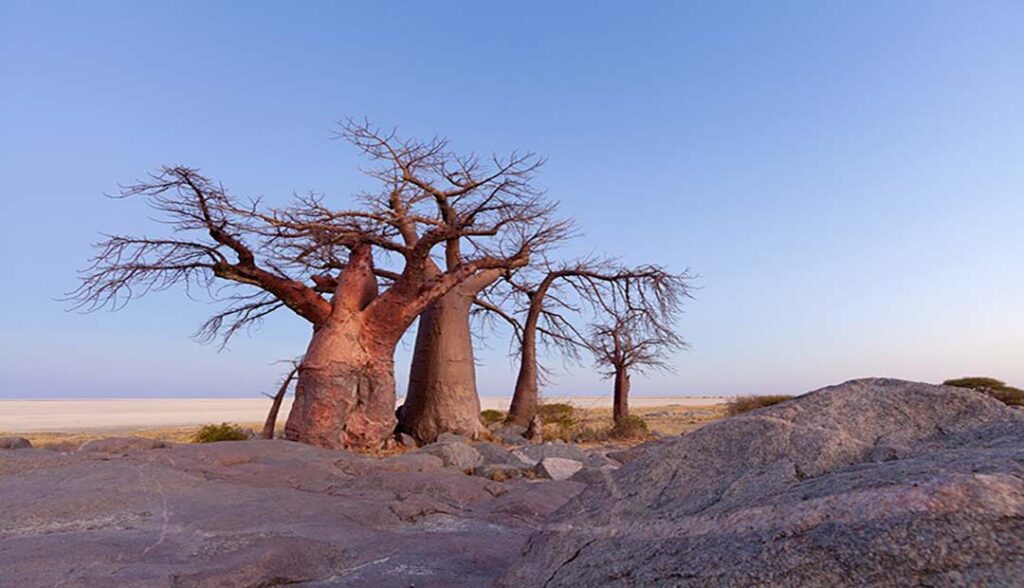

The African baobab tree (Adansonia digitata) is the oldest living flowering plant, or angiosperm, and is found in the continent’s tropical regions. Individual trees — which can contain up to 500 cubic meters of wood — can live for more than 2,000 years. Their wide trunks often have hollow cavities, and their high branches resemble roots sticking up into the air.

The researchers — who published their findings1 in Nature Plants on 11 June — set out to use a newly developed radiocarbon-dating technique to study the age and architecture of the species. Usual tree-ring dating methods are not suitable for baobabs, because their trunks do not necessarily grow annual rings.

The trees’ ages were previously attributed to their size. In local folklore, baobabs are often described as being old, says study author Adrian Patrut, a radiochemist at Babeş-Bolyai University in Romania.

Periodic renewal

Between 2005 and 2017, Patrut’s team dated more than 60 trees across Africa and its islands — nearly all of the continent’s largest, and potentially longest-living known baobabs. To compare the ages of different parts of the trees, the researchers collected samples of wood from the inner cavities and exteriors of the trunks and from deep incisions in the stems, which were then sealed to prevent infection.

Patrut and his colleagues say that their measurements suggest the trees live so long because they periodically produce new stems, similar to how other trees produce new branches.

The team says that over time, these stems fuse into a ring-shaped structure, creating a false cavity in the middle.

But, surprisingly, the scientists also found that most of the oldest and largest baobabs died during the study, often suddenly between measurements.

Nine of the 13 oldest, and 5 of the 6 largest, baobabs measured died in the 12 years — “an event of unprecedented magnitude”, says the study.

The researchers found no signs of an epidemic or disease, leading them to suggest that changing climates in southern Africa could be to blame — but they stress that more research is needed to confirm this idea.

In one instance, the researchers observed that in 2010 and 2011, all the stems of Panke, a giant, sacred baobab tree in Zimbabwe, fell over and died.

The team estimates that the tree was 2,450 years old, making it the oldest known accurately dated African baobab and angiosperm. Other trees across southern Africa also died completely or had partial stem collapse.

Previous research has shown a decline in the number of mature baobabs and a lack of young trees in the region.

Age-old questions

Local experts welcomed the technique for dating baobabs, but some were skeptical of the team’s findings on the die-off. Michael Wingfield, a plant pathologist at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, says that the team’s sample was small and did not provide evidence that baobabs are not afflicted by an epidemic. “We know very little about baobab health,” Wingfield says. “There is much more to this picture than purely the fact that the oldest trees are dying.”

Sarah Venter, a baobab specialist at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, says that her team’s ongoing research shows that baobabs may not be as drought-resistant as previously thought — and this could be the cause of the deaths. But lower tolerance for drought would affect all the trees, not just the largest and oldest ones, she says.