Severe Drought Unveils Ruins of Hidden Ancient ‘Bridge of Nero’ in Rome

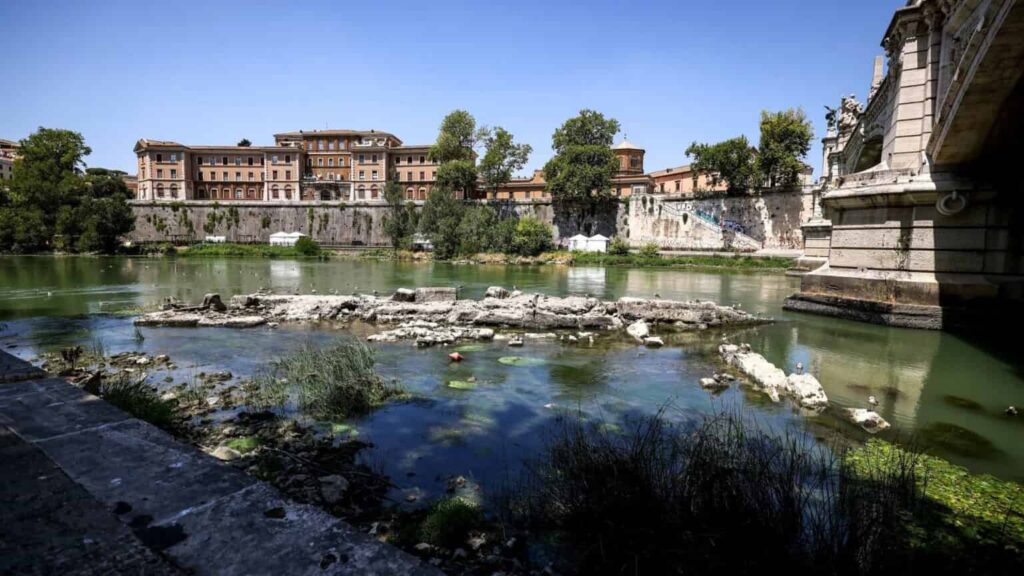

A severe drought in Italy has revealed an archaeological treasure in Rome: a bridge reportedly built by the Roman emperor Nero that is usually submerged under the waters of the Tiber River.

The dropping water levels of the Tiber, which according to Reuters(opens in new tab) is flowing at multi-year lows, have exposed the stone remains of the Pons Neronianus (Latin for the Bridge of Nero), WION News, a news agency headquartered in New Delhi, India, reported.

Emperor Nero, who ruled as the Roman Empire’s fifth emperor from A.D. 54 to 68, was a controversial sovereign who built public structures and won military victories abroad, but also neglected politics and instead focused much of his time and passion on the arts, music and chariot races.

Rome’s coffers were also drained during his rule, partly as a result of building the “Domus Aurea” (the Golden Palace), which Nero built in the center of Rome after the great fire. During his reign, he killed his mother and at least one of his wives, and he struggled to rebuild Rome after a huge fire ravaged the city in A.D. 64. Nero killed himself in A.D. 68 at the age of 30 after being declared a public enemy by the Roman senate.

Live Science talked to several experts, who noted that the remains of this bridge have become visible in the past due to low water levels. They also note that, despite its name, it’s not certain if this bridge was built by Nero.

“The remains of this Roman bridge are visible whenever the water level of the Tiber falls, therefore whenever there are lengthy periods — like now — of very low rainfall,” Robert Coates-Stephens, an archaeologist at the British School at Rome, told Live Science in an email.

Multiple sources told Live Science that the bridge was possibly built before Nero’s rule. “The origins of the bridge are uncertain, given that it is likely a bridge existed here before Nero’s reign and therefore the Pons Neronianus was probably a reconstruction of an earlier crossing,” Nicholas Temple, professor of architectural history at London Metropolitan University, told Live Science in an email.

The name Pons Neronianus “appears for the first time only in the 12th-century catalogues of Rome’s monuments,” Coates-Stephens said. “It’s true that Nero had extensive gardens and properties in the area of the Vatican, and so a bridge at this point would have given easy access to these.”

Bad place to build?

Several scholars told Live Science that the bridge was constructed on a poorly chosen site.

The bridge “was built on a tight bend in a floodplain,” which is “a terrible idea,” Rabun Taylor, a classics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science in an email.

“River bends cutting through pure sediment tend to wander and change shape, so their banks are prone to losing contact with bridge abutments” that connect the bridge to the ground, Taylor said.

He noted that “that’s probably what happened to Nero’s bridge — and it may well have happened by the mid-200s A.D., less than two centuries after Nero’s death.” Taylor’s research into the bridge’s history “suggests the bridge was dismantled at about that time, and the stone piers were reassembled to create a new bridge in a more stable area downstream.

The Pons Neronianus connected Rome to an area that didn’t have a lot of development at the time. While one side of the river had the Campus Martius, a drained wetland that at this point had some public buildings (such as baths and temples), and was used to organize military parades, the other side connected to an area where the Vatican is now that had some large houses.

“It was always good to connect the two banks of the Tiber,” but “the Vatican area was mostly private estates until the Fire of 64,” Mary Boatwright, a professor emerita of classical studies at Duke University, told Live Science in an email. Boatwright noted that it wasn’t until the 130s A.D. that development picked up in the area.

The bridge did, however, have some military and religious importance for Rome, Temple argued. “The Pons Neronianus was both strategically and symbolically important,” Temple told Live Science.

One side of the bridge was located near an area where Roman troops would assemble to march in a triumph (a politically and religiously significant victory parade) and was likely part of the parade route. “The precise route of this procession is uncertain but it seems probable that the Pons Neronianus [and any bridge that preceded it] served as the bridge crossing for this purpose,” Temple said.

This bridge may also have been used to transport high-profile prisoners, Temple added, noting that the crossing may have been “used by St. Peter when he was taken in chains” after his trial to the Vaticanus, where he was crucified in around A.D. 64, Temple said.

“The Pons Neronianus has potentially a double significance, as the crossing point into Rome of triumphal armies, and in the opposite direction for St. Peter’s journey to the site of the crucifixion,” Temple said.

Depending on how climate change affects the Tiber’s water levels, the remains of the bridge may become visible more often. It probably will be visible more often, Boatwright said, adding that “I’d personally rather it be submerged, and Italy not be threatened with drought.”