207-Year-Old Whaling Ship Discovered in the Gulf of Mexico

The wreck of a 19th-century whaling ship has been identified on the sea bottom in the Gulf of Mexico. Its discovery was announced Wednesday (March 23) in a statement released by representatives of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and their partners in the expedition.

Researchers onboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer spotted the wreck on Feb. 25 at a depth of 6,000 feet (1,800 meters).

They used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to explore a seafloor location where the shipwreck had previously been glimpsed, but not investigated, in 2011 and 2017, and their search received additional guidance via satellite communication with a scientific team onshore, according to the statement.

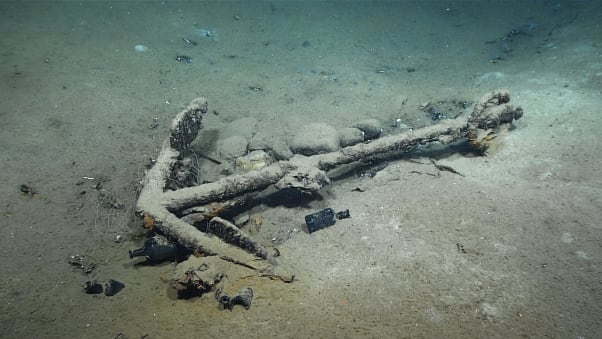

A team of experts then confirmed that the vessel was the Industry, which sank on May 26, 1836, while the crew was hunting sperm whales. It was built in 1815, and for 20 years, the 64-foot-long (19.5 meters) ship had pursued whales across the Gulf, the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean, until a storm breached its hull and snapped its masts.

Though 214 whaling voyages crisscrossed the Gulf from the 1780s until the 1870s, this is the only known shipwreck in the region, NOAA representatives said.

The crew list for Industry’s last voyage was lost at sea, but past ship records show that among Industry’s essential crew were Native American people and free Black descendants of enslaved African people.

The discovery of the wreck could offer important clues about the role that Black and Native American sailors played in America’s maritime industry at the time, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Commerce Don Graves said in the statement.

“This 19th-century whaling ship will help us learn about the lives of the Black and Native American mariners and their communities, as well as the immense challenges they faced on land and at sea,” Graves said.

Life on a whaling ship would certainly have been challenging, with long hours, hard physical labour and poor food that was likely to be infested with vermin, according to the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts.

Living conditions could also be extremely unpleasant; a whaler’s account from 1846 described the crew’s quarters, known as the forecastle, as “black and slimy with filth, very small and hot as an oven,” J. Ross Browne wrote in the book “Etchings of a Whaling Cruise,” according to the museum.

“It was filled with a compound of foul air, smoke, sea-chests, soap-kegs, greasy pans, [and] tainted meat,” Browne wrote.

A deep dive

NOAA’s Okeanos Explorer collects data on unknown or little-explored seafloor regions of the deep ocean, mapping seamounts and discovering mysterious forms of elusive marine life at depths from 820 to 19,700 feet (250 to 6,000 m), according to NOAA.

Past expeditions have revealed “mud monsters” in the Mariana Trench, the “most bizarre squid” an NOAA zoologist had ever seen, and a real-life SpongeBob and Patrick living side by side on the seafloor, Live Science previously reported.

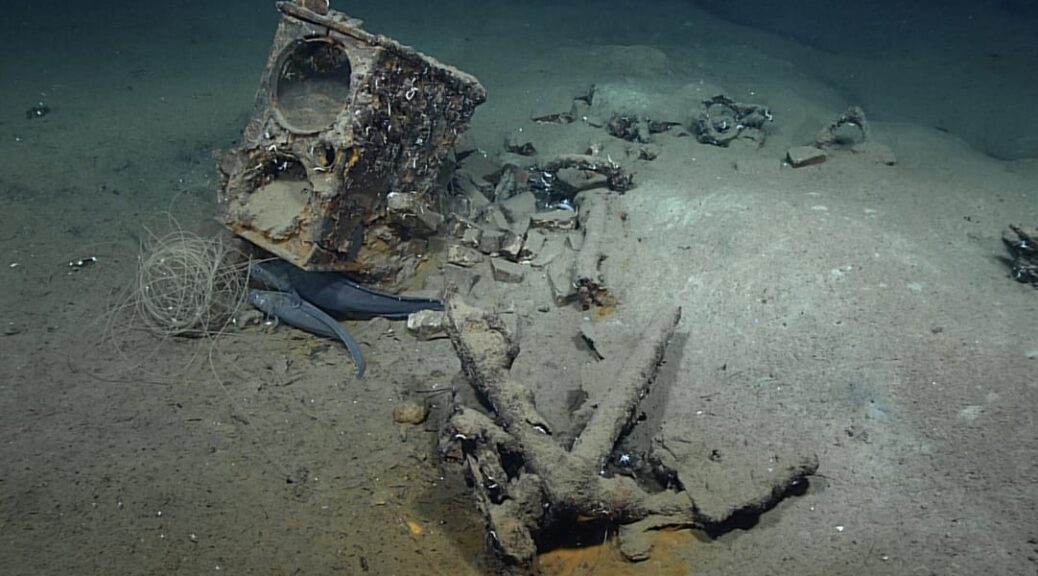

Video from the ROV combined with Industry records enabled the scientists to confirm that they had discovered the long-lost whaling brig.

Another clue that helped experts to identify the Industry was that there was little onboard evidence of its whaling activities; when the ship was sinking, another whaling vessel visited the foundering Industry and salvaged its equipment, removing 230 barrels of whale oil, as well as parts of the rigging and one of the ship’s four anchors, according to the NOAA statement.

“We knew it was salvaged before it sank,” Scott Sorset, a marine archaeologist for the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and a member of the expedition’s shore team, said in the statement. “That there were so few artifacts on board was another big piece of evidence it was Industry.”

New research has also shed light on what happened to Industry’s crew on that final voyage.

Robin Winters, a librarian at the Westport Free Public Library in Massachusetts, unearthed an 1836 article from The Inquirer and Mirror (a Nantucket weekly newspaper) reporting that Industry’s crew was rescued by another whaling ship and brought to Westport.

That was a lucky turn of events for Industry’s Black whalers in particular, who could have been jailed under local laws had they reached shore with no proof of identity, said expedition researcher James Delgado, a senior vice president at the archaeology firm SEARCH.

“And if they could not pay for their keep while in prison, they would have been sold into slavery,” Delgado said in the statement.